AI Agents are here. Security isn’t ready.

AI is no longer just answering questions. It’s taking actions.

At Google I/O 2025, Sundar Pich`ai offered a definition that quietly reset the stakes:

Agents are systems that combine the intelligence of advanced AI models with access to tools, so they can take actions on your behalf, under your control.1

That framing matters, because it marks a shift from AI as software that responds to instructions to AI as software that pursues goals. And that shift is already underway.

Across enterprises, AI systems are moving beyond chat interfaces and single-shot automations toward agentic architectures that can plan, execute, observe outcomes, and adapt their behavior. These agents write code, query databases, operate browsers, interact with CRMs, deploy infrastructure, and orchestrate workflows across systems that were never designed for autonomous decision-makers.

Security, meanwhile, is still catching up to the idea that software can decide what to do next.

Despite the hype, true agentic AI is still early. Industry data shows that only about 16 percent of enterprise deployments and 27 percent of startup deployments qualify as genuine agents2—systems where an LLM plans and executes actions, observes feedback, and adapts over time. Most deployments today are still fixed workflows wrapped around a model call.

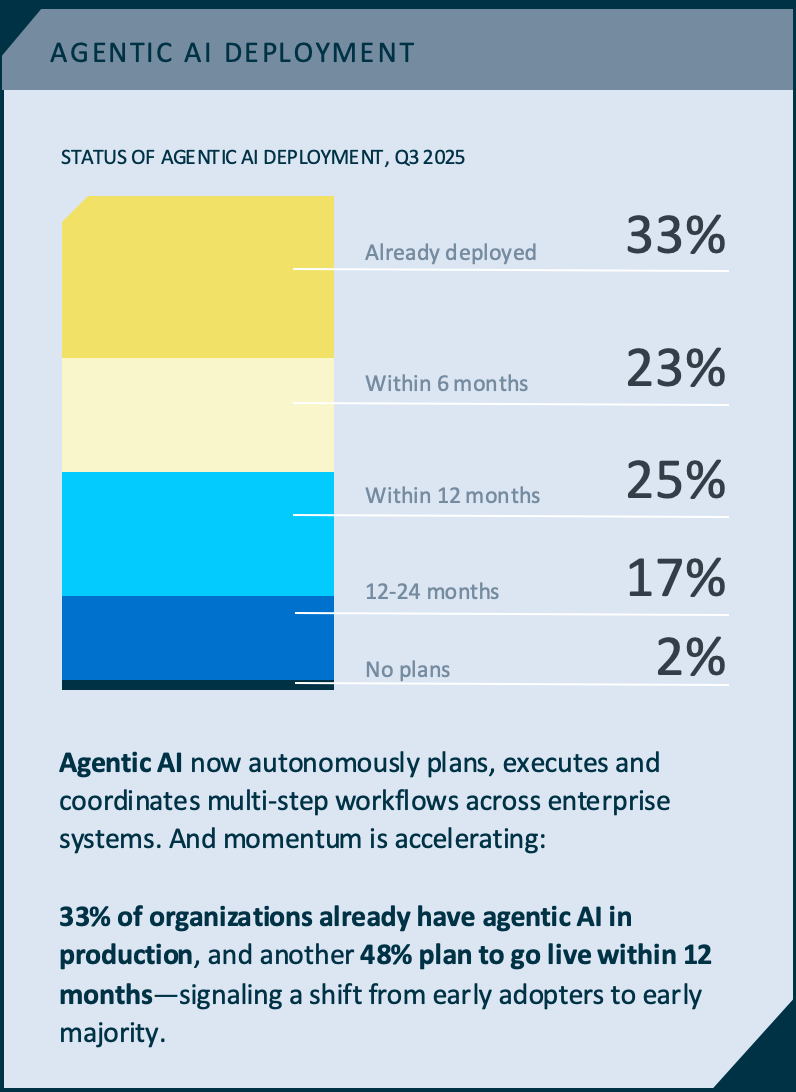

But the adoption curve is steepening fast. By the end of 2025, roughly a third of enterprises had agentic systems running in production, with nearly half planning to deploy within the following year. Almost nine out of ten organizations experimenting with agents reported positive early ROI. At the same time, reasoning-token consumption exploded by more than 300x year over year, a signal that systems are no longer just generating text but reasoning through multi-step tasks at scale3.

Agents rarely arrive as labeled products. They appear as internal tools. CI jobs. Background services. Automation scripts with tool access and an LLM API key attached. To a security team, they look indistinguishable from ordinary services—until they start behaving very differently.

Every major platform shift creates a new kind of shadow IT. SaaS created unsanctioned apps. Cloud created unknown infrastructure. Agentic AI creates something more subtle: autonomous actors embedded inside trusted systems, often without anyone explicitly acknowledging that they’ve crossed from automation into autonomy.

Which leads to the first security failure mode.

Discovery comes before security

You cannot secure agents you don’t know exist.

Discovery in the agentic era isn’t about inspecting code for the word “agent.” It’s about recognizing behavioral signals of autonomy. Long-lived processes that repeatedly call LLMs. Services that dynamically choose tools based on model output. Workloads that chain actions across systems without human prompts at every step.

Traditional asset inventories don’t capture this. IAM systems don’t flag it. SIEMs record events without understanding intent. As a result, many organizations cannot answer a simple question: how many autonomous systems are currently acting inside our environment, and where do they have reach? The closest proxy they use today to try and answer this question is to discover NHIs.

This isn’t a hypothetical risk. It’s the same pattern security teams saw with early cloud adoption, only now the workloads don’t just run—they decide.

Discovery is the prerequisite for everything that follows. Until agents are identified as agents, governance is impossible. And once they are discovered, a second problem becomes unavoidable.

What exactly are they doing?

Observability, rewritten for agents

Traditional observability tells you what happened. Agentic systems demand that you understand why it happened.

Agents operate through non-deterministic reasoning loops. They perceive context, reason about goals, act through tools, and learn from outcomes. Logging an input prompt and an output response captures almost none of that. It doesn’t tell you what the agent considered, what options it rejected, or how it decided that one action was preferable to another.

In security terms, this creates an observability gap. When an agent behaves unexpectedly—querying the wrong data, modifying the wrong system, or triggering a cascading failure—there is often no intelligible explanation available to humans.

This is why agent observability has become its own discipline.

The industry has begun standardizing around richer telemetry models, particularly through OpenTelemetry’s GenAI semantic conventions. These conventions don’t just log requests and responses. They capture tasks and subtasks, tool invocations, intermediate artifacts like generated code or retrieved documents, and the persistent memory that allows agents to carry context across steps.

The result is something closer to a reasoning trace than a log file. You can see the goal the agent was pursuing, the sequence of actions it planned, what it actually executed, and how each decision flowed into the next.

This level of visibility isn’t just useful for debugging. It’s foundational for security. It enables audit. It enables anomaly detection. It enables the most basic form of trust: the ability to reconstruct what happened after the fact.

But visibility alone doesn’t prevent damage. It just helps you understand it.

To prevent harm, agents need to be governed at the points where their reasoning turns into action.

Control starts with identity

The first place control breaks down is identity.

Most agents today operate by impersonation. They inherit a user’s OAuth token. They reuse a service account. They act as “someone else” because existing identity systems don’t offer a better model.

This approach collapses accountability.

When an agent deletes a record, queries sensitive data, or triggers a workflow, security logs show a human user did it. There is no way to distinguish between an intentional human action and an autonomous decision.

Legacy identity protocols weren’t designed for this world. OAuth, SAML, and OIDC assume a human is present, authorizing a specific interaction. Agents don’t behave that way. They delegate to sub-agents. They operate at machine speed. They spin up and down by the thousands. Sometimes they interact with front-end interfaces rather than APIs, leaving no place to pass “on-behalf-of” context at all.

The solution the industry is converging on is authenticated delegation.

In this model, agents receive their own first-class, non-human identities. Those identities are independent of any single user, but every action the agent takes is explicitly attributed to a human or organizational principal through delegated, time-bound authority. The agent authenticates as itself. Delegated authority is conveyed through short-lived, scoped tokens. Audit logs show not just what happened, but who the agent was, who it was acting for, and under what constraints.

This restores accountability. It also enables revocation. If an agent deviates from expected behavior, access can be cut without disabling a human user or breaking unrelated workflows.

Identity is where control begins, but it doesn’t end there.

Continuous authorization: Governing action without killing autonomy

The instinctive reaction to autonomous systems is to lock them down. But agents derive their value from flexibility. Strip that away, and you’re left with brittle automation dressed up as intelligence.

The real challenge isn’t whether to authorize an agent. It’s how often.

Traditional security models assume authorization is a one-time event. A user logs in. A token is issued. Access is granted. From that moment on, actions are implicitly trusted until the session expires. That model collapses in the presence of agents.

Agents don’t perform a single action and stop. They reason continuously. They branch. They delegate. They observe outcomes and adjust their plans. Each step may touch a different system, invoke a different tool, or operate under different risk conditions than the step before it.

In an agentic world, authorization can’t be static. It must be continuous.

Continuous authorization treats every meaningful action as a decision point. Instead of asking “is this agent allowed to run,” the system asks, repeatedly, “is this action allowed now, given what we know?”

That context includes who the agent is, who (or what) delegated authority to it, what goal it is pursuing, what it has already done, and what it is attempting to do next. An agent may be permitted to read data but not modify it. It may be allowed to act for a short window but not indefinitely. It may be authorized to access one system but denied access to another as its behavior evolves. It might be allowed to perform an action if it is acting on a particular user, but not another.

When agents operate locally, continuous authorization governs what they can execute, what files they can touch, and what network destinations they can reach. Sandboxed environments, minimal file systems, and explicit allowlists ensure that even if an agent’s reasoning goes off course, its ability to cause harm is constrained.

When agents interact with other systems, continuous authorization becomes an egress problem. Calls to databases, CRMs, internal services, or MCP servers are not blindly trusted. Each interaction is evaluated against current policy, agent identity, delegated scope, and observed behavior. If context changes, authorization can change with it.

This is where identity, visibility, and control converge.

An agent authenticates as itself. Its actions are observed in context, which includes who it is acting on. Authorization is enforced dynamically, not assumed. Permissions can narrow, expand, or be revoked as conditions warrant—without disabling the agent entirely or breaking unrelated workflows.

The result is autonomy with guardrails. Agents retain the ability to plan and act, but they do so inside a system that never stops asking whether the next action still makes sense.

That shift—from static permission to continuous authorization—is what makes agentic AI deployable in environments where trust, auditability, and control still matter.

For a fun little tool that helps you observe what agents are doing both locally and otherwise, take a look at Leash from StrongDM. Leash is both an observability tool - for a single agent - and allows to allow/deny actions both locally and remotely.

Software no longer just executes instructions. It forms plans, makes decisions, and acts over time. That breaks security models built on static permissions, human identities, and predictable execution paths.

The constraint on agentic AI is not intelligence. It’s control.

Enterprises that cannot continuously discover agents running in their environments, cannot observe what those agents are doing, and cannot continuously authorize their actions will eventually shut them down—or never deploy them in the first place.

The next era of software will be autonomous.

The next era of security must make autonomy governable.

Anything less turns agency into risk.

Excellent breakdown of the control vs. autonomy tradeoff. The continuous authorizaton model is critical but I dunno if most security teams realize how much it shifts the burden from policy definition to policy evaluation at runtime. We're basically asking RBAC to become context-aware at machine speed which is a huge archietctural leap for most orgs.