AI made us faster. That’s not the same as better.

About a year and a half ago, the AI coding landscape was a very different place.

At the time, GitHub Copilot was the category. There weren’t multiple competing models, no real choice of interaction styles, and certainly no sense that AI was a general-purpose programming companion. Copilot lived inside the editor, completed a few lines ahead of you, and mostly tried to guess where your keystrokes were headed. Claude didn’t exist in any practical sense. Codex wasn’t something teams used directly. Chat-based workflows were clumsy, slow, and easy to dismiss as novelty.

So when I pulsed my engineering team about 1.5 years ago about adoption and value of AI coding assistants, I was really asking whether Copilot was effective. The answer then was unsatisfying but honest: sometimes helpful, often marginal, rarely transformative. Adoption was uneven. Productivity gains were hard to isolate. Code quality improvements were unclear. For many engineers, Copilot was fine for boilerplate, occasionally useful for tests, and largely irrelevant for harder problems. The conclusion wasn’t that AI didn’t work—it was that it hadn’t yet earned a central place in the workflow.

Is Github Copilot effective?

It’s been about 90 days since we added a Github Copilot license to every member of my software development team. When Copilot was first introduced, I wanted to assess its impact on the team. Would it yield to more or better code? Would the engineering team be happier or more productive with this novel tool?

Back then we abandoned GitHub Copilot and other similar tools. Fast forward to today, and that framing no longer holds.

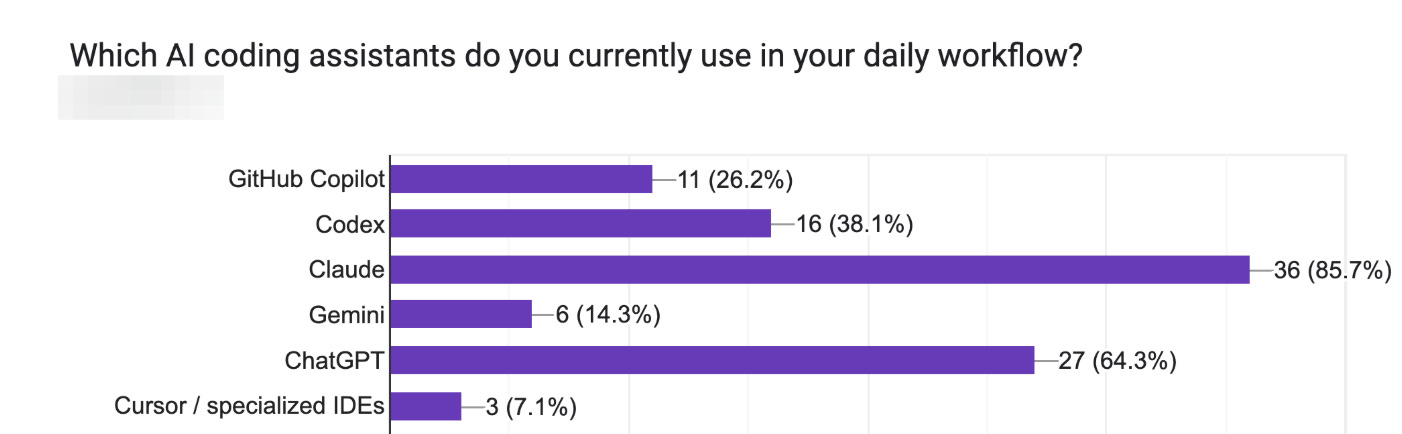

When I recently ran a new survey across the engineering organization, the results reflected that shift immediately. People aren’t debating whether to use AI anymore. They’re deciding which AI to use, when, and for what. That’s a drastic change from the Copilot survey which revealed that most of the engineers weren’t using it.

The most important change isn’t that one tool got better. It’s that the entire tool landscape shifted. AI is no longer a single autocomplete engine living in your editor. It’s a constellation of tools with different strengths, latencies, and interaction models. Engineers move fluidly between chat-based systems, in-IDE assistants, reasoning-heavy models, and increasingly, internal tools designed to apply AI to very specific domains.

Unsurprisingly the most popular tool, which has been true since the release of Sonnet 3.6 in late 2024, is Claude Code. The tools are used daily, often continuously, and across a wide range of activities—from implementation to refactoring to debugging to documentation. Additionally, tool usage is not limited to one. Oftentimes engineers use more than 1 tool, mixing and matching between Claude, Codex, ChatGPT and Gemini.

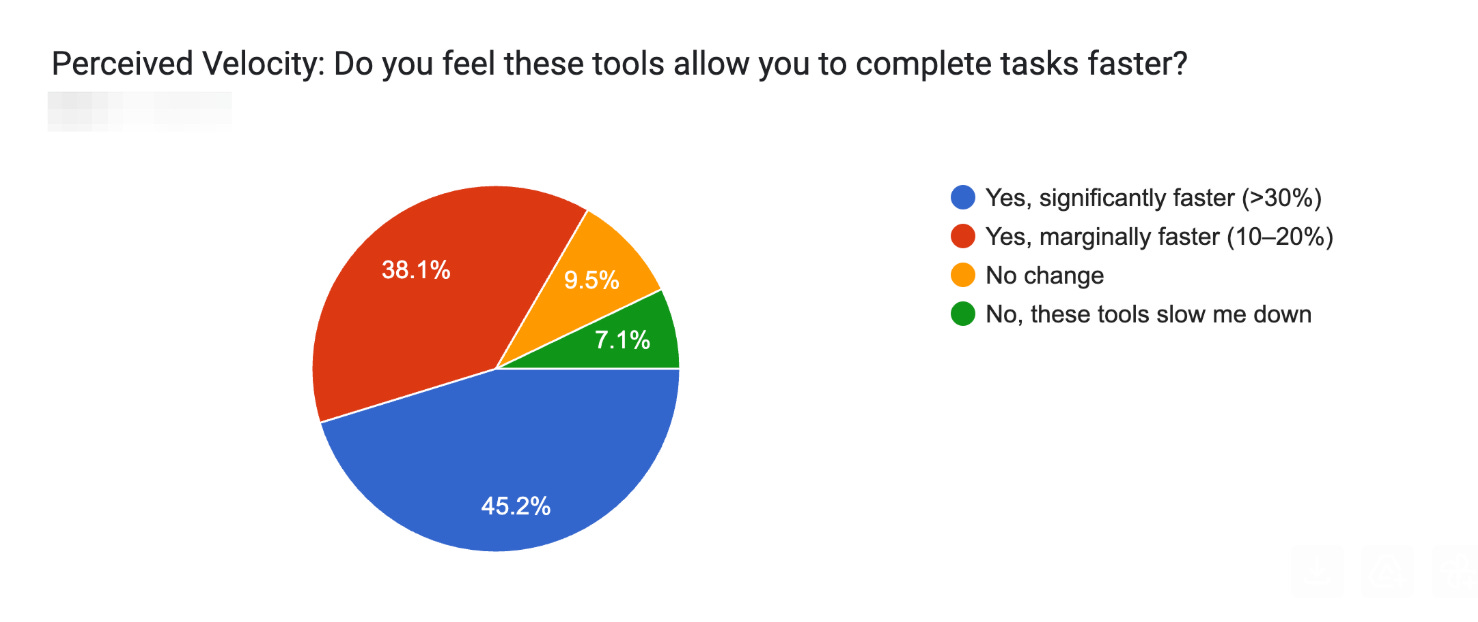

What stood out right away was how clearly engineers felt the speed difference. Compared to the Copilot-era experiment, the perception of increased velocity is no longer ambiguous. Most people feel that these tools help them complete tasks faster, sometimes marginally, sometimes dramatically. From a throughput perspective, AI is now doing real work. The question “does this help me move faster?” has, for most engineers, been answered.

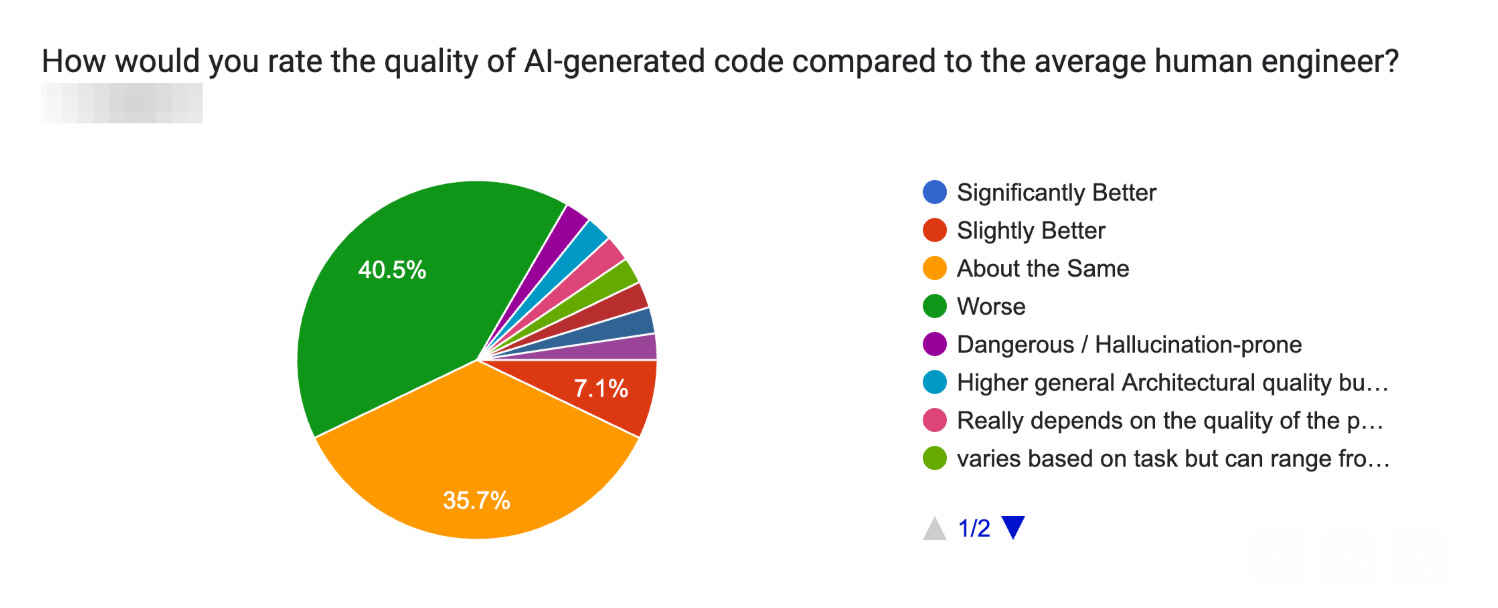

But if the productivity story has sharpened, the quality story has not fundamentally changed.

Despite stronger models and better tooling, AI-generated code is still rarely perceived as superior to human-written code. At best, it’s comparable. Often, it’s worse. Very little of it is considered truly ready to ship without human intervention. Engineers expect to polish it, restructure it, or in some cases discard it entirely. That instinct mirrors what we saw in the Copilot study: AI can accelerate getting something on the screen, but it does not relieve us of judgment, taste, or responsibility.

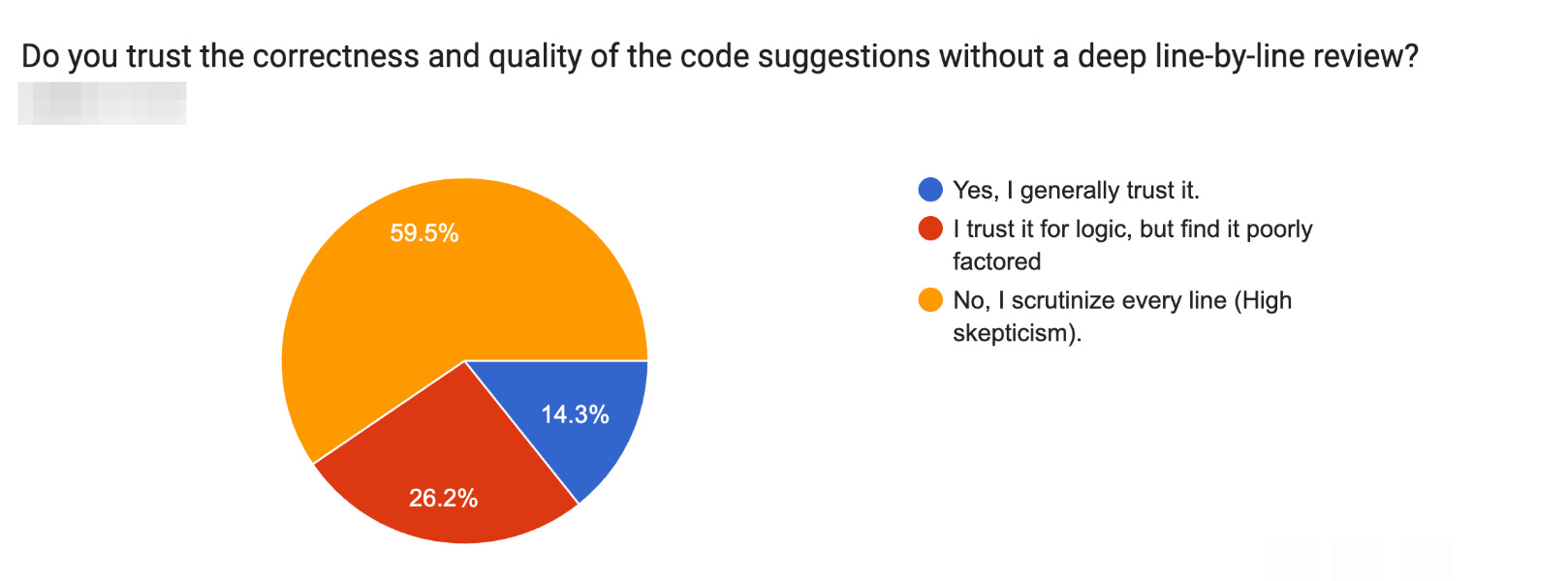

That skepticism shows up even more clearly in how people review AI-generated code. Trust remains low. Most engineers approach AI output with heightened scrutiny, reviewing suggestions line by line rather than assuming correctness. The model may get the logic roughly right, but factoring, clarity, and long-term maintainability still require human care. In other words, while AI has become faster and more capable, it has not been granted a lower bar. Nor should it be.

This is where the real tension emerges. AI shifts work earlier in the pipeline. It compresses the time it takes to produce code, but it doesn’t eliminate the need to understand it. In some cases, it increases the surface area of change, making reviews heavier and more cognitively demanding. Without discipline, speed simply pushes cost downstream—into review, refactoring, and long-term maintenance.

Flow, too, has re-entered the conversation in an unexpected way. The older Copilot model felt instantaneous but shallow. Today’s tools are deeper, but not always invisible. Latency matters. Waiting on responses, switching contexts, or iterating through prompts can interrupt concentration in ways that feel familiar to anyone who remembers long compile times. AI can accelerate progress, but it can also fracture attention if used carelessly.

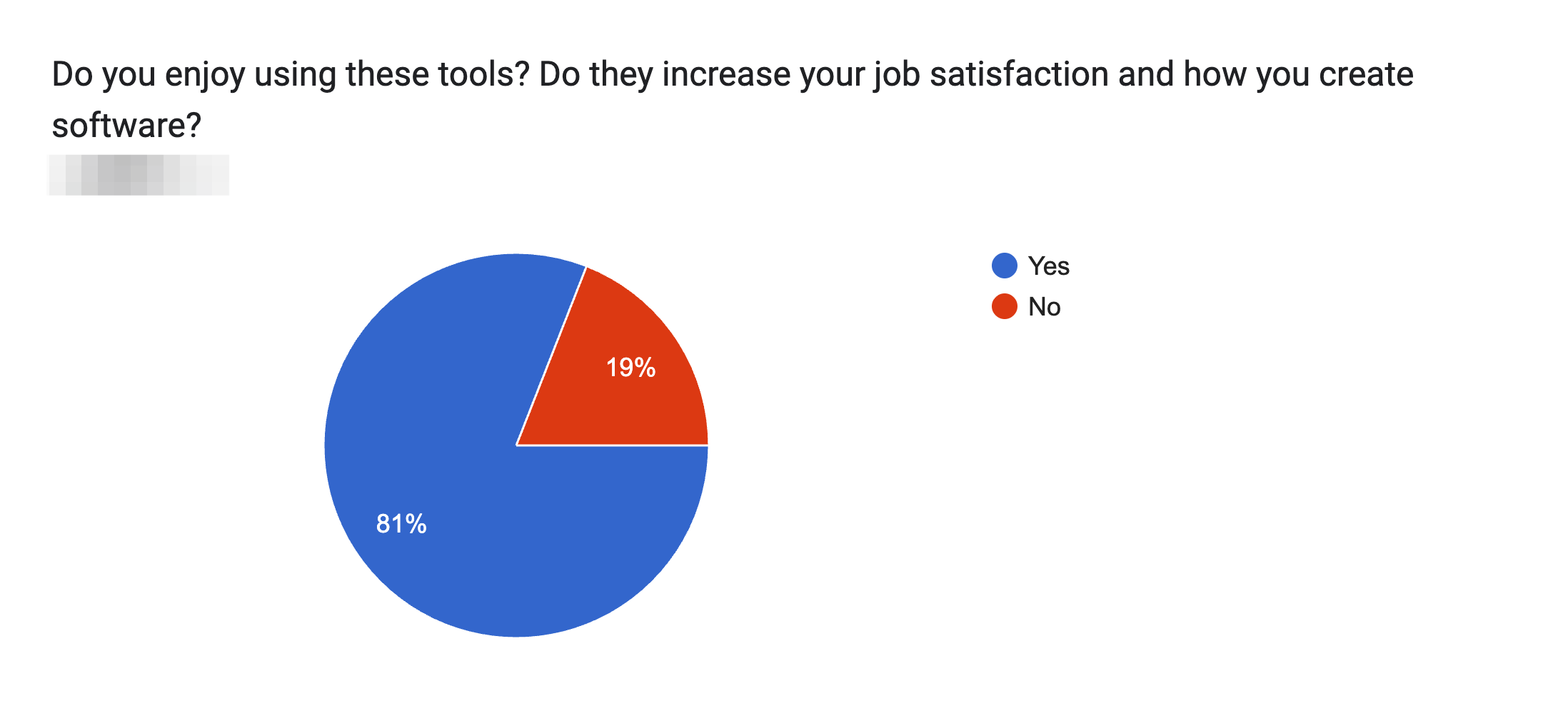

What I found most encouraging in the new survey wasn’t that AI “won,” or that the tools suddenly became magical. It was the maturity of the posture. Engineers understand the trade-offs. They use AI where it helps and disengage when it doesn’t. They move faster, but they don’t pretend that faster automatically means better. The codebase remains a human responsibility. “The AI wrote it” isn’t an explanation—it’s just an implementation detail.

The headline from the Copilot survey was engineers abandoning AI coding assistants.

Today’s headline is markedly different: Engineers are using these tools, perceive productivity gains and generally enjoy using them.

Looking back, the Copilot experiment wasn’t wrong. It was early and the tool was premature. What’s changed since then isn’t the fundamental nature of software engineering. It’s the availability of leverage. AI now meaningfully accelerates parts of the job—but it doesn’t absolve us of ownership. Used deliberately, it makes good engineers more effective. Used carelessly, it amplifies debt.

Agree! I have many uses for AI but it's never "write the production code and YOLO it to prod". But amazing for prototyping, writing one-off scripts, understand new code, generating certain kinds of tests, etc.

It also removes a certain psychological barrier to starting projects, and can be useful for working in the background when I'm going between meetings and don't have the capacity for extended focus.

But there is certainly an antipattern I've noticed of going in circles with the AI when if I'd just sit on myself it might have been clearer how to proceed. Certainly AI slows me down when I'm already in expert in code and what I'm trying to do is well understood.